Image Credit: “Freedom from Want” – The Saturday Evening Post Cover of March 6, 1943, by Norman Rockwell – US National Archives and Records Administration, Public Domain

© 2024 Farok J. Contractor, Distinguished Professor, Rutgers Business School

As Americans sit down to their Thanksgiving Day repasts each year, they are taught to recall the story of the “Pilgrim Fathers,” who in 1620 founded one of the first English settlements in North America at what was then Plimoth Colony in the State of Massachusetts.

But the story of the English settlers seeking religious freedom in the New World was not, initially, one of gratitude. On arriving, they found nothing but “. . . a hideous & desolate wilderness, full of wilde beasts and wilde men.”[1] The settlers thought they had landed on an unexplored and uninhabited frontier, like the Americans landing on a pristine moon more than three centuries later.

Not so, as they quickly found out. The colony was saved from extinction by initially friendly “Indians.” The Atlantic Ocean had been globalized a century before their arrival. And the turkey we consume today is likely not American. Read on…

Early Globalization and the New World

In fact, the very survival of Plimoth Colony, which evolved into the town of Plymouth, as well as the turkey that sits in the center of American tables on the fourth Thursday of each November, are testaments to more than a prior century’s globalization and transatlantic travel. After 1492, when Cristoforo Colombo (re)discovered the Americas (the Norse had already settled in Canada around the year 1,000 under Lief Erikson), the Spanish and Portuguese had crossed the Atlantic thousands of times before the English settlers arrived in 1620; but they had concentrated mainly on the warmer and more fertile colonies in Mexico and Latin America. The English were left with the frigid, seemingly inhospitable remains – the North American forests, which appeared to have little economic value.

Recreation of Plimoth Colony, Plymouth, Massachusetts

The Turkey

The large bird on our Thanksgiving tables is not native to America . . . and certainly not to Turkey. There is no conclusive evidence that any “turkey” was served at the 1621 dinner.[2]

Meleagris gallopavo mexicana – Ancestor of the North American Thanksgiving Bird

The turkey we eat today originated in Mexico, descended from a fowl that the Spanish exported to Europe a century before the English colony in the New World was established.[3] By 1530, this bird could be found abundantly in European and British farms. However, in Europe it was confused with the guinea hen (an African fowl) that had previously been imported into Europe via Ottoman Turkey. Apparently, the taste, and the economics, of the Mexican bird were superior, and thus it displaced the African bird from European farms and tables. It is most likely that what Americans know today as the turkey is the Mexican bird, consumed by Europeans and then later re-imported back to North America on English ships. The Plimoth Colony settlers did hunt fowl, but if their catch included turkeys, it was the North American wild turkey (Meleagris Americana), not the Southern Mexican variety (Meleagris Mexicana) that has been bred into today’s turkey.[4]

Of course, today’s factory turkey is so genetically modified from its Mexican original that it is bland and likely much more tasteless, a far cry from its Mexican progenitor. So extensive has been the selective breeding, that turkeys bred to have larger breasts – for white meat – often cannot stand but topple over.

Singaporeans Celebrating Thanksgiving Day

In teaching in the Rutgers MBA program in Singapore, I have been intrigued, but also a bit sobered, by Singaporean students telling me that they buy Imported American frozen turkey and celebrate Thanksgiving Day, a prime example of globalization and cross-cultural influences.

“Squanto” and the Survival of Plimoth Colony

Tisquantum (“Squanto”), Amazing Young Man of the Patuxet Tribe

Nine months after their arrival, more than half of the 102 individuals that disembarked from the Mayflower had perished of hunger and disease.[5] The utterly unprepared and amateurish Pilgrims had arrived too late in the autumn of 1620 to plant crops, had underestimated the severity of the New England winter, and, to their surprise, found that their landing spot near the Cape Cod peninsula appeared to be unpopulated – so no human help or local advice was available.

In another example of the effects of globalization, the Native American population in the area had been wiped out just a few years earlier through smallpox and other diseases introduced by previously arriving English trading ships. One of these earlier ships in 1608 had sweetly proposed to exchange English metal goods for beaver and other animal skins, but then had captured and enslaved some of the natives and transported them to Europe.

One of them was a young man of the Patuxet tribe named Tisquantum (later shortened to “Squanto”), who was sold as a slave to Spanish Catholic priests for £20. Freed in 1612, Squanto traveled to England and lived in London for six years, with what must have been a wild hope of returning to his native village. In fact, it was not so improbable an aspiration because globalization was by then well established. Each year, English ships would travel to New England to trade, pillage, and enslave. In 1618, Squanto’s English-language abilities and general acumen were noticed by an English ship captain who offered to take him back to New England in return for his translation and intermediary skills. Landing somewhere near the State of Maine, it took Squanto three years to walk his way south and find his native village (the place called Plimoth by the Pilgrims).

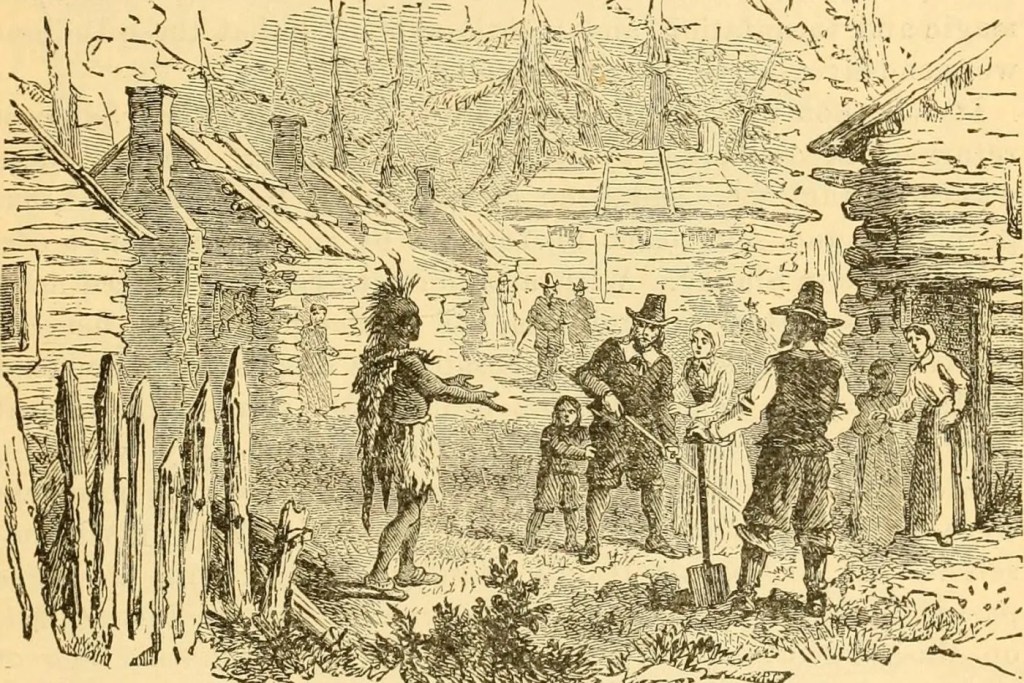

In the spring of 1621, as despair and death faced the weakened remaining English settlers, to their utter amazement a Native American – Squanto – greeted them in English, as well as the area’s Wampanoag language. He stepped into their settlement, offering them friendship and advice on what crops to plant and how to hunt and trap animals. More importantly, Squanto served as an ambassador, or bridge, to the region’s Narragansett and Wampanoag Indians, so that for a remarkable half century there was an uneasy peace between the English and the natives.

Squanto Greets the Surprised English Settlers

But by 1675, with more than 22,000 English immigrants, the natives realized they were being displaced from their own lands, so they launched an attack under the leadership of Metacom. This is sometimes described as the First Indian War. Of course, the locals were no match for English guns and growing numbers of colonists. The English presence in North America was by now an unassailable presence, whose later growth would populate the continent from “sea to shining sea.”

Thanksgiving – A Globalization and Unity Story as Well as an American One

Americans who enjoy their Thanksgiving repast are mostly oblivious of the fact that the story of the very founding of the United States is very much a story of globalization. Squanto’s transatlantic journeys, his role in enabling the English settlement on the American continent, and the export and re-importation of the Mexican bird known to us as the turkey are vivid examples that globalization was commonplace – and even routine – by the 17th century.

Cynics may smirk at cross-cultural influences, such as Singaporeans celebrating Thanksgiving, or even Asian Indians and Chinese observing Valentine’s day, another example of globalization. (Valentine was, in legend, a fourth-century saint in Italy who promoted love and marriage.) Nowadays, every February 14th sees a boost in the sales of flowers, cakes, and gifts in places such as Beijing, Mumbai, and Singapore.

Putting cynicism aside, globalization does unite us, at first superficially, but on closer inspection by making “other” cultures appear more sympathetic, less hostile, and more like fellow humans sharing the same planet.

Wishing readers everywhere a Happy Global Thanksgiving.

Also see Plimouth Patuxet Museums, including “The Winds of Change,” an animation of the “First Thanksgiving”

[1] From the diary of William Bradford (1590–1657), 1620: “A Hideous and Desolate Wilderness.” In History of Plymouth Plantation.

[2] What Food Was Served at the First Thanksgiving in 1621? | Smithsonian

[4]John Bemelmans Marciano. On the origin of the species: Where did today’s bird come from? The answer may surprise you. Los Angeles Times, November 25, 2010.

[5] In 1621, only 50-odd half-starved survivors were left of the 102 that disembarked from the Mayflower. But despite losses, with later arrivals the number of English grew to 180 by 1624, increasing to over 1500 by 1650. (Patricia Scott Deetz and James Deetz, Population of Plymouth Town, Colony & County, 1620-1690.)