Click 23 Mar 2020 for update

©2020 Farok J. Contractor, Rutgers Business School

Around the world, governments are reacting to the spread of the coronavirus by recommending, or forcing, the closure of schools, restaurants, and travel. By having the population remain at home, the much-reduced human-to-human contact will slow down the spread of the virus.

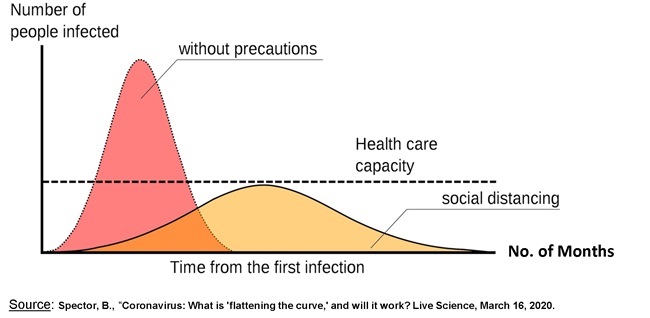

The underlying idea as seen in the figure below is that a nation has only so many hospital beds, doctors, and medical facilities, and can – at one time – handle only so many cases. The dotted line in the graph shows a country’s maximum healthcare capacity. The pink zone shows that, without precautions, the maximum daily number of people infected would be greater than the healthcare capacity of the nation and overwhelm it.

A Sample Epidemic Curve, With and Without Social Isolation

NOTE: “No. of Months” has been added.

On the other hand, with forced isolation, or social distancing, the trajectory of infections is supposed to follow the yellow zone in the graph and “flatten” or lower the maximum number of daily cases of COVID-19 (coronavirus disease-2019) so that the healthcare capacity of the nation can cope with the maximum number of cases. But that then can extend the duration of the pandemic, as well as prolong and deepen a recession.

After its somewhat belated response, the federal government is now planning for as much as an 18-month duration of the pandemic.[1] And there is a huge difference between a recession that lasts for only six months and one that extends to 18 months, not just in terms of bankruptcies and layoffs, but also in the health costs of unemployment and personal lack.

The Excruciating Dilemma: “Social Isolation” Can Also Increase and Worsen the Coming Global Recession

The excruciating dilemma for governments is that by “flattening the curve,” they may be prolonging the number of months the pandemic lasts. We really do not know, but the longer it lasts, the longer the duration of the global recession – with an increase in the horrendous financial (and health) consequences that a longer recession would entail.

Recessions and unemployment also cause excess mortality, as a number of socioeconomic and healthcare studies show.[2] Layoffs caused by company failures and bankruptcies also cause mental depression, drug dependence, alcoholism, morbidity, and diminished educational attainment, whose effects ricochet in each country for years to come.

Frankly, I am not sure that many governments have even thought through this dilemma: the trade-offs between the physical health of the populace, versus the financial health of the economy, versus the political consequences of either a shorter or a longer pandemic and recession.

The Unknowns and Trade-offs

Moreover, until more data come in,[3] we do not have an exact idea of the total impact of forced isolation or social distancing for this particular virus. Here are some unknowns:

- Are the areas under the pink curve and yellow curve the same? That is to say, will imposed isolation and “social distancing” actually reduce the number of persons who get infected, or simply spread them out over more months in the future? The figures in the above graph are a schematic representation. It is too early to deduce how the virus behaves, whether the number of infections under social isolation (yellow zone) would be lower than without government mandates (in the pink zone), or indeed whether a recurrence would occur in winter 2021.

- Regardless of the number of infected persons, would the number of fatalities be lower under the yellow curve versus the pink curve because hospitals would not be overwhelmed? If so, the current government policies of imposed isolation make sense from a humanitarian perspective (if not, perhaps, an economic one).

- On the other hand, by “flattening the curve” and increasing the duration of the pandemic, the financial hardship on companies and people would also – because of economic reasons – increase the number of fatalities out into the future. (We know that unemployment and stress increase health risks.)

- Until more data come in, we simply do not know (at the time of this writing) how or if the Northern Hemisphere summer season would slow the spread of the virus.

The Most Effective Answers

The best response, of course, would be to raise the height of the dotted line in the graph. That is to say, if the capacity of a nation’s healthcare system were raised and maintained above the maximum number of cases that needed to be handled, then the dilemma between the health needs of the population and creating a recession would be lessened.

Take Singapore as an example of a government that acted preemptively and early. As of March 20, 2020, Singapore had only 385 cases, zero deaths, and no lockdowns. The recommended maximum size of a gathering or conference was a rather relaxed 250 persons.[4] (This may change as the situation is fluid. However, by comparison, my workplace, Rutgers University, is shut down, classes are all online, and gatherings of more than 15 persons are not allowed, resulting in the cancelation of graduation ceremonies and other events. At Florida International University, the limit is three persons in a room.[5])

Of course, Singapore has a population of only 5.7 million, but its economy is one of the most globalized, highly integrated with the rest of the world. Singapore has the world’s highest Trade/GDP ratio of around 400 percent,[6] and commerce plus tourism resulted in 19.11 million international visitors in 2019.[7]

While not strictly comparable, other nations can learn some lessons from how Singapore is handling the epidemic:

- Advance Preparation: Learning from the 2002−2003 SARS epidemic, Singapore built enough isolation hospitals and stockpiled test kits.

- Early Government Response: Unlike the Trump administration’s delayed response,[8] in early January Singapore began to mobilize doctors, nurses, test kits, test centers, screening protocols at entry points, etc.

- Intensive Tracking: Once cases developed, a special department of several hundred tracking personnel, aided by computer surveillance, sprang into operation. Each person with a suspected case of COVID-19 is required to answer a thrice-daily text message by responding with their location.

- Harsh Penalties: The relatively few who are isolated face severe fines if they misreport their location and condition.

- Compliant Population: Singapore’s citizens are reputed to be among the world’s most orderly and compliant.

- Trust in Government: Singapore’s government is by no means the most open. However, over the decades, when it has spoken or made an announcement, the message has typically been accurate. This trust is part of the reason why its citizens comply with their government’s recommendations or directives.

Conclusion

For most nations, regrettably, the early-reaction window seems to be closing. The policy dilemma for governments is how much to shut down and isolate – “flattening the curve” – and thus likely extending the economic downturn versus following more relaxed policies, which means more mid-term cases and possibly greater political backlash.

Because we know so little about the behavior of the virus at this stage (as of March 20, 2020), it is difficult for anybody to judge the trade-offs. It is possible that history may judge the shutdowns in many countries as an overreaction that produced enormous economic and long-term health damage. Or the shutdowns may be deemed by historians as having been appropriate – at least for those nations that reacted too slowly at the beginning of the outbreak.

[1] Bublé, C. (2020). Coronavirus roundup: Federal response could last 18 months. Government Executive, March 18.

[2] For example: Hone, T., Mirelman, A., Rasella, D., Paes-Souza, R., Barreto, M., Rocha, R., & Millet, C. (2019). Effect of economic recession and impact of health and social protection expenditures on adult mortality: a longitudinal analysis of 5565 Brazilian municipalities. The Lancet, 7 (11). Or: Jofre-Bonet, M., Serra-Sastre, V., & Vandoros, S. (2018). The impact of the Great Recession on health-related risk factors, behaviour and outcomes in England. Social Science and Medicine, 197, 213−225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.010

[3] This article was written on March 20, 2020, when most nations were early in their infection cycle.

[4] Kok, Y. (2020). Coronavirus: “Nuclear option” of lockdown highly unlikely in Singapore. Straits Times, March 20.

[5] But in the Florida International University student cafeteria, the only restaurant open on campus (at least on March 13, 2020), there were apparently more than 100 persons in the room.

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trade-to-GDP_ratio

[7] https://www.statista.com/statistics/977993/total-international-visitor-arrivals-singapore/

[8] Bouie, J. (2020). Don’t let Trump off the hook. New York Times, March 20.