© 2021, Farok J. Contractor, Distinguished Professor, Management & Global Business, Rutgers Business School

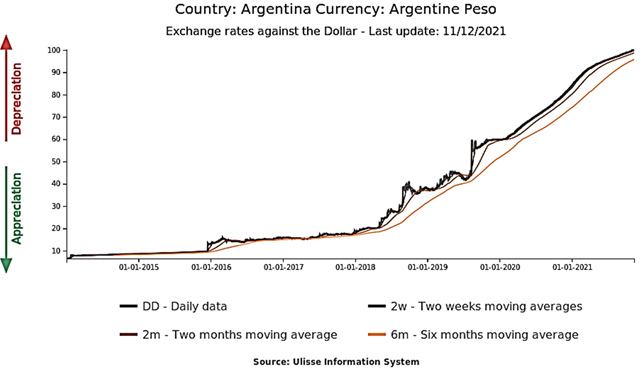

On November 8, 2021, it happened — as predicted by the purchasing power parity (PPP) theory: the Argentine monetary unit crossed the symbolically important threshold of 100 pesos = 1 US dollar (USD).

A lurid but sad tale. A century ago, some predicted that Argentina would soon join the ranks of advanced nations. Instead, populist governments, freewheeling borrowing and spending, and mismanagement of its economy resulted in high inflation in much of Argentina’s modern history. And PPP theory tells us that when inflation is higher than in a country’s trading partners, this will inevitably result in a devaluation of the currency.

We can trace the history of the Argentine peso from a mere 1 peso = 1 USD in 2001 to this week’s symbolic (or shall I say “shambolic”?) marker of 100 pesos = 1 USD — a hundredfold devaluation of the currency in only two decades, as shown in the graph.

The Argentine peso has been overvalued for most of its history. (“Overvaluation” simply means “not enough devaluation.” In this case, it refers to the Argentine government either “fixing” the exchange rate by dictat or fiat or, as in recent years, preventing or slowing down devaluation of its currency.) An overvalued currency results in shrinking export earnings, an exaggerated artificial demand for imports, and a burgeoning trade deficit. Eventually, it reaches the point where hard currency earned from exports does not even cover absolutely vital imports.

Then a government such as Argentina temporarily tries to keep sustaining the trade deficit by (a) borrowing USD from the IMF or international bond markets and/or (b) imposing a rationing system whereby the country’s banks restrict convertibility (i.e., allow only a few high-priority importers to exchange pesos for dollars so that at least some necessary imports can continue). The knock-on effect of denying convertibility to all is that an unofficial or parallel market emerges for currency exchange, euphemistically called the “Dólar Blue” in the graph below:

Source: StudiaBo elaboration on Exportplanning and Bluelytics data.

The bigger the gap between the parallel market and official rates, the stronger the signal that the economy is under greater strain and a devaluation is coming.

Like many emerging-nation governments, Argentina, to sustain necessary imports, has repeatedly borrowed billions of dollars from international bond markets by offering to pay high interest rates on its bonds in excess of, say, 10 percent per annum. (The bonds are pieces of paper or electronic entries with promises by Argentina to repay principal plus interest back to the investors in dollars.) This attracts suckers and risk-takers into paying dollars and buying Argentine bonds, even though the country has defaulted nine times in its history — seven times in the past 100 years, and twice since the year 2000. When Argentina defaults, the value of it bonds plunges to a fraction of the face value, and bond holders are left with “paper” that is worth less — or, in some cases, worthless (i.e., zero value).

For a review of Argentina’s recurrent defaults, see the Bloomberg article One Country, Nine Defaults: Argentina Is Caught in a Vicious Cycle by Ben Bartenstein, Sydney Maki, and Marisa Gertz (September 11, 2019, updated on May 24, 2020). Also see my previous posts on this subject: Argentina Seems Headed for Another Currency Crisis (and Perhaps Default), October 16, 2020, and Advantages and Drawbacks of Undervalued Versus Overvalued Currencies, January 29, 2019.

This is a cautionary tale for other emerging-country governments — and some would say even for the US government (although any such debt problems would likely not occur in the US until well into the distant future, to be taken care of by as yet unborn generations of Americans).

The bottom line is that, in the long run, PPP theory inevitably works.