© 2016 Prof. Farok J. Contractor, Rutgers Business School

A version of this post also appeared as a featured article at YaleGlobal Online

Also listen to the Podcast Where Do Brexit and Anti-Globalization Sentiments Come From? Recorded by Hira Jafri, Director of Global Programs, Yale MacMillan Center and see 11/26/19 Post

angst noun: “a feeling of deep anxiety or dread, typically an unfocused one about the human condition or the state of the world in general”[1]

![]()

The UK—an almost insignificant island on the western edge of the Eurasian landmass—is a tiny economy, making up only 2.36 percent of the world GDP.[2] Why does it matter that they are leaving the European Union (EU)? Because the 52 percent vote to exit the EU is symbolic of a larger angst that has swept many parts of the world. From the US, where Donald Trump wishes to wall off the rest of the world; to Turkey, where what used to be a secular nation has turned more fundamentalist, with head scarves and hijabs more in evidence; to India, where a Hindu-first party swept the polls in 2014.

So why is much of humanity feeling more anxious lately? “Globalization,” a somewhat fuzzy term, encompasses increased trade and immigration to some, and the perceived threat of job losses and a slight erosion of sovereignty when nations sign treaties or join economic blocs. But behind globalization is the deeper issue of each individual’s sense of identity.

The Threat to Identity

Who am I? This question has afflicted and worried human beings from the dawn of history. But it has only been in the 21st century that mass media images of rusting factories being abandoned, millions of refugees marching into foreign lands, crazed killers spraying citizens with automatic weapons, and politicians exploiting all of these anxieties have penetrated the consciousness of voters in many countries.

Who am I? was once a question that was answered by most of humankind by identifying with their families, their villages or small towns, their religious institutions, and their cultural cocoon within a radius of 50 miles. Even today, English accents in the UK vary every 25 miles (with many native Brits altering their own accents to “the Queen’s English” to improve their career prospects).[3] And the majority of Britons rarely see, let alone interact with, foreigners, since most immigrants are concentrated in major cities such as London or Bristol. (Both cities voted to remain in the EU, with decisive majorities. The foreign-born population makes up 12 percent of the UK, of which 4.6 percent were born in other EU nations.) Most Hindus (81 percent of India’s population) who vote for Hindu-first parties that describe Muslims as a threat have no personal dealings or interaction with Muslims or other minorities.

The Unbalanced Role of Media

Media companies are businesses that need to make profits. And fear sells. Anxiety captures attention and views. Millions of slanted emails and Facebook posts, with no fact-checks or attributions, circulate around the world. Images of terrorist incidents transfix billions of viewers and create a false sense of insecurity and xenophobia. Even counting the unusual number of 2,902 deaths during the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Towers, fatalities from terrorist incidents in the US over a 20-year period (1995–2014) averaged only 158 per year.[4]

By contrast, each year in the US more than 35,000 die in auto accidents, over 11,000 from firearm assaults, about 2,700 from falls off ladders or stairs, over 30 from earthquakes, and around 25 from lightning strikes.[5] As a result, people around the world have a highly distorted picture of relative risks, which vastly exaggerates the perceived danger from “foreigners” that most have never met and will never encounter.

Loss of Sovereignty

International trade and closer economic ties inevitably mean voluntarily giving up a smidgen of sovereignty. Imports take away local jobs and leave behind hulking shells of abandoned factories. But what politicians like Boris Johnson (a champion of “Brexit”) calculatedly fail to tell their public is that jobs created by Britain’s exports and investment abroad create even greater employment opportunity (often with better pay) than the lower-paying jobs destroyed by import competition.

For healthy economies like the US and UK, unemployment in mid-2016 was a mere 5 percent or below—a rate that economists consider, practically speaking, to be full employment because the 5 percent includes persons between jobs or traveling to their next assignments. Donald Trump, while criticizing China, never speaks of the hundreds of billions in annual benefits to American customers from less costly goods, or the fact that fruit and vegetable prices could triple without migrant labor. And Boris Johnson did not mention how much higher the plumber or the mechanic’s bill would be were it not for Polish and Romanian immigrants who have entered these occupations.

True, EU regulations have vexed some British businesses, but this is hardly an issue since one’s own government, in an advanced society, will have to regulate its businesses. Tellingly, in the “Brexit” debate, the media mainly interviewed small business owners—bakers and butchers—who grumbled about EU regulations. Executives in larger firms were overwhelmingly in favor of remaining in the EU.

Here again, the issues are more psychological than logical. Globalization and economic growth, in the past 35 years, have changed many businesses and individuals from more or less complete freedom to having to fill out forms, seek permissions, and face bureaucratic obstacles.

Bureaucracy is national, not supranational. Almost all regulations in the world are imposed by one’s own government and not foreign sources. Bureaucracy is often the reaction by governments to demands from their own public for better safety or ethical dealings. To attribute loss of economic or individual autonomy to foreign sources is false.

“Lies, Damn Lies, and Statistics”

Globalization does mean that a nation “loses some and wins some.” But in return for a tiny loss of sovereignty and some more scrutiny, regulation, and foreign competition, most nations’ consumers and businesses—on average—benefit. The “gain” for almost all nations considerably outweighs the “pain”—again, on average.

But when we speak of statistical “averages,” herein lies the rub: the gain and pain are never spread equally over a country’s population. Nor are the gain and pain equally visible to the public. Most shoppers at Marks & Spencer in the UK or Macy’s in the US do not realize that the family saves hundreds or thousands per year because poor wretches in Bangladesh or Burundi toil on their behalf at less than 40 cents per hour, or that perhaps one in six jobs in their country are a result of international business. Such benefits are dimly seen, if ever, being diffused over many shopping visits and spread over a population of 64 million in the UK and 325 million in the US.

What is more visible is the concentrated suffering of a few thousand workers laid off at Port Talbot[6] or the rusting hulks of factories in Detroit. The news media do not find it glamorous to report on the lower prices from imports enjoyed by Walmart shoppers. But the grief of layoffs is newsworthy. Pain, fear, and anxiety sell more advertisements than an abstruse calculation of consumer benefits.

“Averages” are dangerous statements. A nation is typically better off from globalization. But the internal distribution of benefits and costs, of the gain and pain, are never equitable.

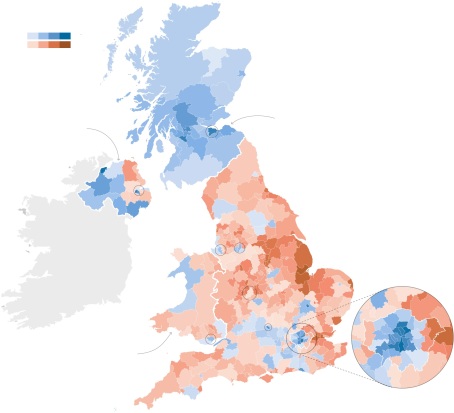

The map of the UK, showing which districts voted for “Brexit,” paints a telling picture. In the past 20 years, while all of the UK public has enjoyed lower prices and higher quality from imported goods—and “on average” Britons are better off—most job growth and wealth accumulation have been in large cities such as London or Bristol. The rest of the UK has also progressed, but less so. Internal disparities between the cleaned-up metropolitan areas, their cosmopolitan elites, and the rest of the UK have deepened.

No wonder, then, that the “remain in the EU” vote was concentrated in richer urban centers—the blue zones in the map below. The orange and brown shires are envious of the metropolises. These outlying regions also, ironically, have far fewer foreign-born persons. Nevertheless, they are also more fearful, exhibit greater angst, are less educated, and are more willing to listen to one-sided arguments from politicians exploiting xenophobia for their own career advantage.

How Britain Voted in the EU Referendum

Source: New York Times, June 24, 2016

Statistics may deceive. But, alas, in the more anxious world created by globalization, things such as fear-based Internet media, outright lies, untruths, and phobias can find easier acceptance—even in seemingly well-educated populations in advanced nations.

The remedy, as always, is more truth-telling.

![]()

[2] GDP as Share of World GDP at PPP By Country: Quandl.com.

[3] Many change accent to get ahead: BBC News, January 22, 2009.

[4] University of Maryland Center for Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism: American Deaths in Terrorist Attacks. National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) Fact Sheet, October 2015.

[5] National Center for Health Statistics, National Safety Council: Mortality RIsk: Odds of Dying from Accidental injuries. Insurance Information Institute, 2013.

[6] Tata Steel confirms 1,050 job cuts: Layoffs in 2016 by Tata Steel in 2016 in the face of cheaper Chinese steel imports: BBC News, January 18, 2016.

Bravo! Tagi

Tagi Sagafi-nejad Professor emeritus, Loyola University Maryland (956) 206-3351

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks much on behalf of Farok, Tagi! Pam

LikeLike