© 2018, Farok J. Contractor, Rutgers Business School

An earlier version of this article was published on this site on May 5, 2016, and also in AIB Insights, Vol. 16, No. 2 (2016).

Recommended Citation:

Contractor, Farok J. Tax avoidance by multinational companies: methods, policies, and ethics. Rutgers Business Review, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 27–43 (2016).

Also see related posts: The [2016] G20 Summit in China: An Annual “Talking Shop”? Or a Potential Bedrock of Global Civilization? and Tax “Amnesty” for Multinationals—But Not for Illegal Immigrants.

This article outlines several tax-avoidance techniques used by multinational corporations (MNCs) and the government policies that enable them, followed by a discussion of ethics and corporate responsibility. The tax-avoidance phenomenon, amounting to hundreds of billions each year, affects global operations, supply chains, and location decisions—placing this issue at the heart of global strategy.

There is no world government or supranational tax authority. A world fragmented into more than 190 nations (each seeking local optimization of revenues) is in tension with MNCs that look on the entire world as their blank canvas (global optimization) and fall prey to the temptation of using the tax-avoidance techniques outlined here.

![]()

Introduction: Why This Review of International Tax Issues Should Be Read by Business Executives

To most executives, scholars, and teachers, global taxation may appear to be an obscure topic. But actually, it is central to global decision-making because most foreign direct investment (FDI) and global operations these days are biased by tax considerations. The numbers are huge. For instance, with around $10 trillion worth of world trade being intrafirm and a similar portion being intermediate (as opposed to finished products or services), it is the multinational firm that gets to decide internally what unit price it will type on its export invoice. No “arms-length” equivalent benchmarks are easily available.

Because of a US tax provision, between $2.1 and $3 trillion in accumulated profits of US multinationals’ foreign affiliates have not been repatriated back to the home country. I conservatively estimate that out of the million-odd subsidiaries or foreign affiliates[1] of all multinationals listed in the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) 2015 database, between 300,000 and 400,000 are shell or dummy companies (firms that have no economic activity except a part-time accountant or a lawyer behind a shining brass nameplate). The entire FDI inflow statistics of major nations such as China or India are biased by the “round-tripping” of local investment masquerading as foreign investment.

Global strategists and international business (IB) scholars grapple with a key dilemma—the tension between a world divided into 190-odd territorial and tax jurisdictions versus the desire of multinational corporation (MNC) executives to look upon the planet as a single economic space within which to optimize by shifting taxable profits, operations, and finance from one country to another. Awareness and sensitivity about international tax avoidance are growing, exemplified by the EU’s introduction of a “Tax Avoidance Package” in 2016,[2] and by strident voices on the American right—Trump labeling corporate inversions as “disgusting”)[3]—and left—Sanders describing tax avoidance as a “scam.” Executives, however, argue that it is their fiduciary duty to maximize shareholder value by taking every advantage of provisions and loopholes available under various countries’ laws.

An Overview of Tax-Avoidance Methods and Their Relative Importance

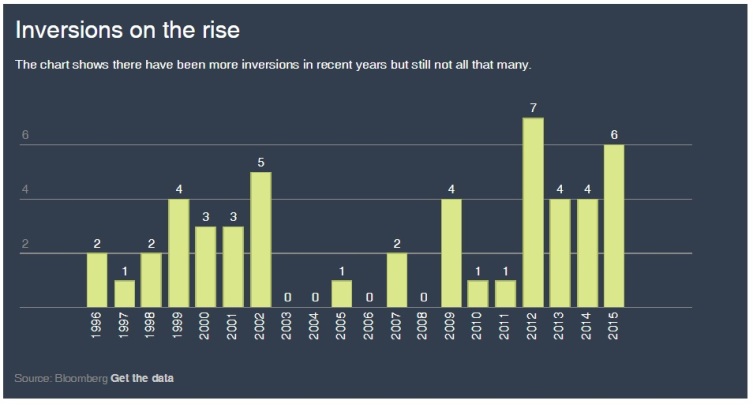

“Inversions” have been much in the news, at least in the US, such as the planned $150 billion merger between New York-based Pfizer and Dublin-based Allergan, torpedoed by the Obama Administration’s new rules in April 2016.[4]

In simple terms, an inversion involves a company shifting its corporate headquarters from a higher-tax nation by merging with a firm in a lower-tax jurisdiction, such as Ireland (whose tax rate is 10–12.5 percent). But despite eliciting pseudo-patriotic opprobrium, the number of large inversions has actually been very few, less than 50 since 2000.

In simple terms, an inversion involves a company shifting its corporate headquarters from a higher-tax nation by merging with a firm in a lower-tax jurisdiction, such as Ireland (whose tax rate is 10–12.5 percent). But despite eliciting pseudo-patriotic opprobrium, the number of large inversions has actually been very few, less than 50 since 2000.

The tax-avoidance methods summarized in the examples below, starting with the ones that have the biggest impact, are mostly legal because they use provisions and loopholes granted by the countries involved.

1. Exemption of Foreign Affiliate Income from Additional Home Country Tax

Most advanced nations typically tax multinational home-country operations, but do not additionally tax profits of the company’s foreign affiliates (Markle, 2015). This is the biggest tax benefit for multinational companies—being able to pay corporate tax only in each nation where the profits are earned. Some other countries treat the multinationals’ worldwide income (home nation as well as foreign) as taxable.

The US used to be an example of this policy, in theory making US companies’ foreign affiliate profits additionally taxable in the US.[5] No longer. The US now does not additionally tax foreign affiliate profits.

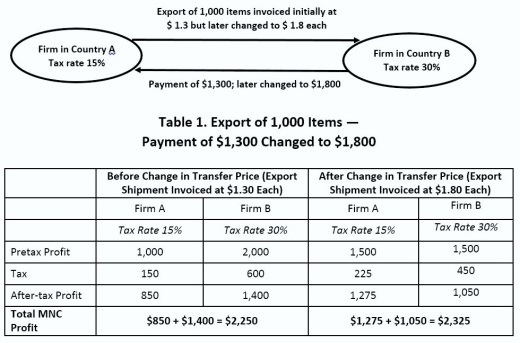

2. Transfer Pricing (Invoice Values)

In international supply chains, multinationals ship goods and services whose unit value, decided by the MNC itself, is often biased by tax considerations. Consider two firms, A and B, both owned by the same MNC. Firm A has been exporting 1,000 items per year to Firm B, invoiced at $1.30 each. But if they are invoiced at $1.80 each, B would then pay A $500 more annually. Firm A’s profit would increase, and B’s would decrease; but the MNC as a whole would increase its after-tax income from $2,250 to $2,325. The idea is simple: pay higher amounts to affiliates where taxes are lower, and show lower values where taxes and/or tariffs are higher. (See Table 1.)

Table 1. Export of 1,000 Items

No real change has occurred, except for just one keystroke—when typing the invoice, “8” is entered instead of “3” (1.8 instead of 1.3).

The above is only one example. Millions of shipments are made annually—a great many where the exporter and importer are the very same MNC, which can internally decide on the invoice value depending on the tax differential between the import and export nations. Intrafirm trade is huge, estimated to range between 42 and 55 percent of world trade (around $23 trillion). Moreover, much of international trade is not in finished, but in intermediate, products—some with unique designs and embedded proprietary technology—so that no comparative arms-length valuations are possible, and the MNC itself declares the shipment’s value (Lanz & Miroudot, 2011).

In the above example, if Firm A’s country’s tax rate were higher than Firm B’s, or if A’s country levied an import tariff, then the situation would be reversed: the MNC would be tempted to under-value the shipment to reduce its total worldwide tax and tariff liability.

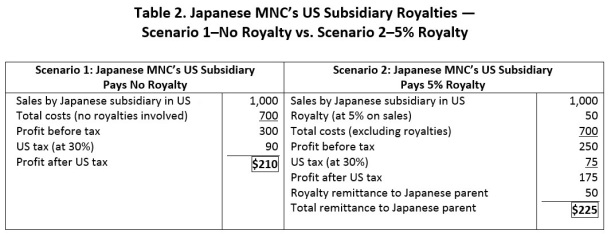

3. Royalty Payments

Tax avoidance through interfirm royalty payments occurs because of three salient facts:

1. Typically, MNCs are technology-intensive, and most value resides in their proprietary technologies or intangible assets.

2. Even if research and development (R&D) costs have been incurred by Firm A (say the home country of the MNC), current rules allow the transfer of the patents or brands to a holding company or subsidiary (in a low-tax country, such as Ireland) or a shell company (in a zero-tax country, such as Bermuda), which then charges royalties to headquarters and other affiliates (Dischinger & Riedel, 2008).

3. Most governments allow deductions for royalty payments, which reduces tax liability to the licensee—even if the licensee is part of the same MNC, and even if no R&D had been performed in the licensee’s nation.

First, we will review a simple example of how interfirm royalties reduce tax liability. A Japanese company, having done its R&D in Japan, establishes a subsidiary in the US. In Scenario 1, the US subsidiary pays no royalty for the Japanese technology. In Scenario 2, nothing has changed except that the Japanese parent has signed an additional side agreement with its US subsidiary, which will then pay a 5 percent royalty to its parent. Under US rules, despite the US operation’s being the fully owned “child” of its Japanese “parent,” the royalty payments are a deductible expense. US tax liability is legally reduced from $90 to $75. And the total remittance (after-taxes) to Japan increases from $210 to $225. (See Table 2.)

Table 2. Japanese MNC’s US Subsidiary Royalties

Less re-investible profits are left in the US operation, and more goes to Japan. The side royalty agreement makes sense if the effective tax rate in Japan (say 20 percent) is less than the US tax rate of 30 percent.

What makes even more sense (from an aggressive tax-avoidance point of view) is for the Japanese MNC to transfer the patent rights to its subsidiary in a lower-tax nation, such as Ireland. By making the Irish operation the licensor and collecting the royalties there, they would be taxed at an even lower corporate tax rate—perhaps as low as 10 percent instead of the Japanese tax rate of, say, 20 percent (Mutti & Grubert, 2009).

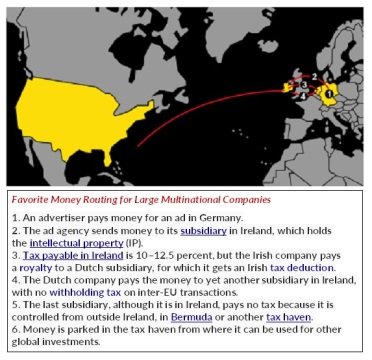

Pushing the envelope further, despite the R&D’s having been done in Japan or the US, the patent and brands could be transferred to a Bermuda or Cayman Islands shell company—as Google, Apple, and many pharmaceutical firms have done—with royalties collected there at near-zero tax liability. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Favorite Money Routing for Large MNCs

Source: Wikipedia, Double Irish arrangement

Graphic Image by Maxxl2 – Own workNews.com.au, GFDL

4. Intracorporate Loans

Another provision governments offer companies is deducting interest payments on loans as an expense item. Indeed, paying interest is an expense for the borrower/payer. But if the lender (source of funds) and borrower are companies within the same MNC, albeit in different nations, then the MNC has a clear path to paying less tax in high-tax jurisdictions—it can make its lower-taxed affiliates extend loans to its affiliates in higher-tax nations and can then enjoy a juicier tax deduction on the interest payment.

FDI flows consist of three components: FDI Flow = New Equity + Retained Earnings + Net Intracorporate Loans. Although we lack comprehensive data on the magnitude of the stock of worldwide intracorporate loans, they would very conservatively exceed three quarters of a trillion dollars (UNCTAD, 2015). We have no comprehensive idea of how many loans are motivated by tax avoidance, and even less about the extent to which the intracorporate interest rate deviates from the actual cost of capital to the lending affiliate or parent. Clearly, if the intracorporate interest rate set by the MNC internally is higher than, or lower than, the actual cost of capital, the MNC has another tax-liability-transference device. In recent years, “…a number of countries have imposed restrictions on the tax deductibility of interest…” (DeMooij, 2011); but the enforcement of rules is lacking, especially in developing nations (Faccio, Lang & Young, 2010).

5. Other Central MNC/Parent Overheads and Costs

An inescapable fact of modern multinational business is that significant costs, especially having to do with R&D, are incurred by the parent firm, which then logically has to charge some fraction of its central overheads to each of its foreign subsidiaries and affiliates (Sikka & Willmott, 2010). For reasons scholars have not fully understood, the R&D expenditures of MNCs remain highly clustered in the parent firm nation, or at least in far fewer countries than the number of territories in which the fruits of the R&D are derived (Belderbos, Leten & Suzuki, 2013).

As we saw in Technique 3 above, charging royalties to each affiliate for centrally developed technology is one technique. But other categories of overheads, such as the costs of maintaining brand equity, and other central administrative costs at headquarters, such as global information technology, supply-chain management, human resources, etc., should not be borne entirely by the parent firm. Rather, they should be spread over the various subsidiaries and foreign operations that enjoy the benefits of the MNC’s central administration overheads.

In principle, this sounds fair. But in practice, how does the MNC carve up slices of its central overheads pie and proportionally allocate (charge) a slice to each foreign affiliate? Even trying to be globally equitable (and tax unbiased) is difficult because the allocation or proportion will vary depending on the weight of each foreign operation (in the planetary total). The calculation depends on whether the weighting for each country is based on numbers of employees, versus value added in the nation, versus assets, and so on.

An obvious further complication is that exchange rates fluctuate, affecting the share of each affiliate in the worldwide total pie from year to year.

But, of course, MNCs are not unbiased. They face a clear temptation, ceteris paribus, to allocate a larger slice of the overheads pie to operations in higher-tax nations and vice versa. There is no standard methodology. The EU has been attempting, since 2000, to formulate relevant rules for a unitary (pan-European) system for the future. But each formula has its problems and detractors (Picciotto, 2012; Altshuler, Shay & Toder, 2015).

6. Other Uses of Tax Havens: “Round-Tripping” and Evading Currency Convertibility Restrictions

We saw above how tax havens in zero- or low-tax countries such as Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands, or the Cayman Islands can be used to incorporate shell companies. Such companies serve two functions: (1) They can hold the MNC’s patent and brand rights. (2) And they can serve as the licensor to collect royalties charged to other affiliates globally—this reduces their taxes because each affiliate claims a deduction in their nation for the royalties paid, while the royalties collect tax-free in the tax haven.

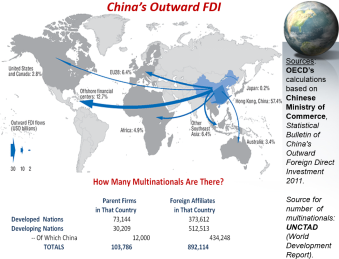

Some tax havens and low-tax nations are used for “round-tripping.” According to the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2013), as much as 57.4 percent of China’s outbound FDI capital in 2011 went to Hong Kong affiliates or subsidiaries, and another 12.7 percent went to Caribbean entities. That means that as much as 70.1 percent of Chinese outbound FDI capital flows, exceeding $100 billion per year since 2011, have gone to two tiny economies—the Caribbean and Hong Kong. (By contrast, Chinese companies’ direct FDI outflow to European or US affiliates was a mere 8.2 percent of the Chinese total.)

Some tax havens and low-tax nations are used for “round-tripping.” According to the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2013), as much as 57.4 percent of China’s outbound FDI capital in 2011 went to Hong Kong affiliates or subsidiaries, and another 12.7 percent went to Caribbean entities. That means that as much as 70.1 percent of Chinese outbound FDI capital flows, exceeding $100 billion per year since 2011, have gone to two tiny economies—the Caribbean and Hong Kong. (By contrast, Chinese companies’ direct FDI outflow to European or US affiliates was a mere 8.2 percent of the Chinese total.)

So what happened to the 70.1 percent of Chinese outward FDI that went to Hong Kong and the Caribbean? Much of this Chinese money made a round trip, returning to mainland China under the guise of “foreign investment” in order to take advantage of the still slightly better terms (e.g., tax breaks, cheaper land, loans) offered by the Chinese central and provincial governments to “foreign” as opposed to purely “domestic” investors. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2. China’s Outward FDI

Sources: OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard 2013. UNCTAD World Investment Report, 2011.

Another driver for the Chinese FDI outflow is the desire by Chinese companies and rich individuals to evade currency convertibility restrictions (Contractor, 2015). One cannot convert the Chinese renminbi (RMB) into dollars or euros without a written justification. Creating a dummy subsidiary in Hong Kong or the Caribbean provides that justification, on the grounds that capital has to be sent out to support the Chinese parent’s foreign operations.

Note: More recent data at this level of detail are not available. However, the same situation and incentives still exist so that many Hong Kong and Caribbean subsidiaries continue to serve the dual purposes of (1) tax avoidance and (2) overcoming currency convertibility limits.

As a result, UNCTAD (2011) reported an implausible number of Chinese foreign affiliates: as many as 434,248 out of a worldwide total of 892,114 affiliates for all MNCs. One has to conclude that a large majority are shell companies, with no economic activity or purpose other than round-tripping and evasion of capital controls.

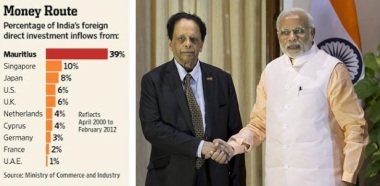

It is not just China. For Europe, OECD (2015) reports that such “special purpose entities” (SPEs, or shell companies) account for more than 80 percent of FDI into Luxembourg and the Netherlands, more than 50 percent in Hungary, and more than 30 percent in Austria and Iceland. Around a third of FDI into India used to emanate from Mauritius because the two countries had a tax treaty. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3. The Prime Ministers of Mauritius and India Seal a Deal

Sources: Simply Decoded and The Economic Times, India

Considering these facts, I conservatively estimate that 30–40 percent of all FDI affiliates worldwide in the UNCTAD World Development Reports or World Bank databases are shell companies—a sobering thought for analysts and scholars using these data. And my estimate may, in fact, be low.

7. Inversions

In simple terms, an inversion involves a company shifting its corporate headquarters to a lower-tax jurisdiction by acquiring/merging with a foreign firm in a lower-tax country. For large multinational companies, the annual savings can be in the billions, as illustrated by the aborted Pfizer (US)-Allergan (Ireland) merger in April 2016.[6] In Ireland, corporate taxes max out at 12.5 percent, which is lower than many advanced nations. Other examples since 2012 include Mylan moving to the Netherlands, Burger King to Canada, and Medtronic to Ireland—all of which had lower tax rates than the US.

Politicians of all stripes labeled inversions as unpatriotic. Announcing rules in April 2016 that make such foreign takeovers much tougher,[7] President Obama described inversions as “insidious” and added that “…fleeing the country just to get out of paying their taxes… [American MNCs] benefit from our research and our development and our patents. They benefit from American workers, who are the best in the world. But they effectively renounce their citizenship.”[8]

For all the political bluster and opprobrium, the numbers of inversions have been very few, and now after 2018 with reduced tax rates in the US, they are likely to be very rare. For the US, six were completed in 2015, up from four in each of the previous two years. (See Figure 4.) As long as MNCs have the perception that home nation taxes are higher than in other nations, inversions will continue in the future.

Figure 4. US Corporate Inversions

Source: The Conversation: Crackdown on corporate inversions highlights monstrosity of U.S. tax code, April 20, 2016

How Good Are Government Enforcement and Audits?

There is an awakening realization (at present confined to the EU and OECD Secretariats) that a considerable disconnect exists between the desire of governments to collect reasonable revenues from companies in each territory or region (local optimization) and the desire of MNCs to ensure shareholder interests by “arranging” investments, supply chains, and invoices to minimize global tax payments (global optimization).

What about audits? Despite nascent intergovernmental cooperation and exchange of information, for the most part governments can audit tax filings only within their own territories. Even in terms of “audits,” governments face a stark practical reality. Each year, for the world as a whole, multinational companies and their affiliates file around one million tax returns. In all the governments on the planet—including rich countries such as the US, Japan, and Europe—there cannot be more than a couple of thousand auditors or inspectors that view or scrutinize MNC returns.

Only a very tiny percentage of tax filings are read by a human (although some advanced nation governments use special artificial intelligence software programs, or algorithms, that flag anomalies or egregious outliers). There is no “world tax authority,” and even the exchange of information between governments is only just a trickle. This means that MNCs can, and do, push the envelope to minimize global tax payments, their proclivities limited only by ethical self-restraint.

Ethical Pros and Cons: The Corporate and Governmental Perspectives

Many executives believe that corporate taxes are already too high and that taking advantage of loopholes to reduce payments is legitimate. And many would also argue that the company’s fiduciary duty to maximize shareholder interests is paramount, and that taking advantage of provisions and loopholes is legal and ethically defensible.

The corporate viewpoint generally is that:

- MNCs paying high taxes suffer a competitive disadvantage vis-a-vis firms located in lower-tax nations. Paying higher taxes means less money is left over, and this in turn means:

– Shareholders get smaller dividends, and

– Less is put back into R&D—which ultimately determines the competitiveness of the firm in global competition.

- Paying taxes only encourages profligate governments to spend more money on other programs.

- If government rules allow certain loopholes, it is the company’s fiduciary duty toward shareholders to use such loopholes to (legally) avoid tax payments.

During mergers/acquisitions for “inversions,” the change of domicile is only for tax purposes—necessary operations and jobs would remain in the original nations.

Critics of MNC behavior argue that:

- Tax avoidance may be legal, but is not ethically defensible because many of the loopholes and tax provisions have been written to favor corporate interests by lobbying and political influence on the part of the companies. Critics assert that, even prior to 2018, the much-trumpeted US corporate tax rate actually was not 35 percent—that was only the marginal rate on the last slab of income, with average effective rates variously estimated to be not more than 19.4 percent (according to Citizens for Tax Justice[9]) or 27 percent (according to Price Waterhouse[10]). This put the US tax burden in the middle of the OECD advanced-nation group. Since 2018, under the new tax law, US corporations effectively enjoy a well-below OECD nation tax burden.

- Multinationals enjoy several other tax-avoidance schemes, outlined in this article, such as international licensing (royalty payments) between affiliated entities, charging central fixed costs and overheads to various foreign affiliates, creating intracorporate loans or export shipment “transfer-pricing,” and tax-haven subsidiaries.

- It is true that if a MNC pays less tax, more money is left over for shareholder dividends or to put toward replenishing the R&D budget. But critics argue that higher after-tax profits from tax avoidance may be diverted instead into fatter bonuses and stock options for top executives.

- Inversions may maintain necessary jobs and operations in the original countries. However, shifting the headquarters of the company increases the chances of additional job creation in the other nation or elsewhere.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) for Multinationals?

The dilemma multinational company executives face is how to reconcile the ethical desire for the corporation to contribute something to each country in which it operates with the need to maximize global total earnings, after taxes, for shareholders. Large firms operate in dozens of nations (and recall that there are more than 190 nations in all). But shareholders of each company are still concentrated in one or few countries.

From a CSR perspective, a company should contribute something of value to each nation in which it conducts business. Paying reasonable taxes to each government is one type of contribution, which would enable the nation’s government to build roads, support education, and so on. But a multinational firm can make other types of contributions to a country, such as helping to upgrade local technology and skills, building up ancillary or supplier firms to multiply the local economic impact of the foreign investment, and transferring best practices in a range of areas from effluent standards to logistics to human resource management and training. All contributions the MNC makes to a nation need not be monetary. But in focusing on global after-tax profit maximization, the net welfare of each individual nation is often forgotten by the company.

Solution? My recommendation would be that each company appoint a Global CSR Officer (CSRO), whose staff would annually calculate—for each nation—the net benefit (monetary and non-monetary) contributed by the MNC. The CSRO would be senior enough and have sufficient clout to “push back” against the tendencies of the CFO (Chief Financial Officer) or the company’s Treasury Department to engage in global after-tax profit maximization, heedless of individual countries’ interests.

This dilemma between the interests of shareholders, typically concentrated in one or a few headquarter nations, versus the interests of each country or market the MNC operates in is only going to get more acute with greater awareness and publicity through social media.

Conclusion

No decision in large MNCs is made these days without assessing tax implications. The magnitude of the international tax-avoidance phenomenon—the extent to which global operations, supply chains, and location decisions are affected by tax considerations—places this issue at the heart of global strategy. In large companies, executives consider tax angles concurrently with strategy, rather than as an afterthought. Consequently, an acquaintance with this topic is absolutely essential to students of business and to all executives.

There is no world government or supranational tax authority.[11] A world fragmented into more than 190 jurisdictions (nations) is at odds or is in tension with MNCs that look on the entire world as their blank canvas (Contractor, 2014), are willing to relocate operations wherever it suits them, and may fall prey to the temptation of using the tax-avoidance techniques outlined in this article.

![]()

References

Altshuler, R., Shay, S. E., & Toder, E. J. (2015) ‘Lessons the United States Can Learn from Other Countries’ Territorial Systems for Taxing Income of Multinational Corporations’, Available at SSRN 2557190.

Belderbos, R., Leten, B., & Suzuki, S. (2013) ‘How global is R&D [quest] firm-level determinants of home-country bias in R&D’, Journal of International Business Studies, 44(8), 765–786.

Contractor, F. (2015) ‘Seeking Safety Abroad: The Hidden Story in China’s FDI Statistics’, Yale Global. September 10.

Contractor, F. (2014) ‘Global Management in a Still-Fragmented World’, GlobalBusiness.me, October 7.

DeMooij, R. (2011) ‘Tax Biases to Debt Finance: Assessing the Problem, Finding Solutions’, IMF Staff Discussion Note, May 3rd.

Dischinger, M., Riedel, N. (2008) ‘Corporate taxes, profit shifting and the location of intangibles within multinational firms’, Munich Discussion Paper, No. 2008–11.

Faccio, M., Lang, L., Young, L. (2010) ‘Pyramiding vs leverage in corporate groups: International evidence’, Journal of International Business Studies, 88–104.

Lanz, R., Miroudot, S. (2011) ‘Intra-firm Trade: Patterns, Determinants and Policy Implications’, OECD Trade Policy Working Paper No. 114.

Markle, K. (2015) ‘A Comparison of the Tax‐Motivated Income Shifting of Multinationals in Territorial and Worldwide Countries’, Contemporary Accounting Research.

Mutti, J., Grubert, H. (2009) ‘The effect of taxes on royalties and the migration of intangible assets abroad’, in International trade in services and intangibles in the era of globalization by Reinsdorf, M. & Slaughter, M., University of Chicago Press. 111–137.

OECD (2013) ‘OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard 2013’, OECD iLibrary 2013.

OECD (2015) ‘How Multinational Enterprises Channel Investments Through Multiple Countries’, OECD Statistics. February.

Picciotto, S. (2012) ‘Towards Unitary Taxation of Transnational Corporations’, Tax Justice Network. December.

Sikka, P., Willmott, H. (2010) ‘The dark side of transfer pricing: Its role in tax avoidance and wealth retentiveness’, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 21(4), 342–356.

UNCTAD (2011). World Investment Report 2011 (United Nations publication, Sales No. Sales No.: E.11.II.D.2).

UNCTAD (2015). World Investment Report 2014 (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.14.II.D.1).

![]()

Pamela M. Bond Contractor

May 16, 2016 at 5:14 pm

Thanks for this pingback to our GlobalBusiness.me post.

Reply

cgcanton

May 16, 2016 at 5:28 pm

Thanks to you, great piece

LikeLiked by 1 person

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

LikeLiked by 1 person